Exclusive details: The bizarre legal fight between AHS and landlords – one of which is an AHS employee

Posted May 11, 2018 6:36 am.

Last Updated May 11, 2018 6:43 am.

This article is more than 5 years old.

Imagine walking out of the shower of the home you share with other tenants. Your hair still wet, wearing a bathrobe as you walk to your room. Except there’s Alberta Health Services inspectors and Calgary Police in the living room. An inspector has been in your bedroom, because apparently under the Public Health Act, it’s considered a public dwelling. You have no idea why they’re there.

What’s described is one of several accounts by tenants of two landlords with grievances dating back five years according to court affidavits, transcripts and other documents. Since last summer, 660 NEWS has been tracking the ongoing and sometimes bizarre legal fight and has exclusive details about the landlords, their tenants and AHS. Despite some minor victories from time to time in the courts, the group has often been on the losing side, commonly unable to find lawyers who would pick up their case, with most claims either being discontinued or dismissed according to AHS counsel. But the landlords have found a new lawyer, which they hope will turn the tide.

What makes the incident more unusual is that one of the landlords involved is an AHS employee herself.

DIFFERING POSITIONS

AHS has never acknowledged any wrongdoing, arguing the inspections were matters of public health and safety, pointing the finger at the tenants’ common thread: their landlords Daiming (Robert) Li and Lily Wang. The now-separated couple owns multiple properties in Calgary and have been both applicants and defendants in different actions against AHS. AHS lawyers have argued in cross-examination Li and Wang went so far as manipulated affidavits and that they made vexatious and wasteful legal claims.

But what makes the case even more unusual is Wang is an employee of AHS herself, serving as an analyst for the last six years. In a November interview, Wang described the experience.

“If I use one sentence to describe the whole thing, it’s no life over the last four or five years, no life, it’s horrible,” she said, arguing AHS has tried to portray them as slumlords.

As for her position with the organization, she says she works in a different department than the one the health inspectors operate in. She also said she utilized her organization’s own programs for the depression and anxiety she’s dealt with.

“My work has nothing to do with them and no connections and I have never personally contacted any, the public health inspectors for personal matters,” she said.

While AHS has been the undisputed victor in the overall battle between both sides, despite its ample resources against tenants with little money and virtually no legal expertise, a few of their attempts to impose penalties and win costs haven’t been successful. However in the grand scheme of the dispute, Li and Wang were ordered to pay over $120,000 in costs. They are still appealing decisions.

Much of the fight revolves around specific sections of the Public Health Act and what is considered public and private places. Under the Section 60 of the Act, it says a health inspector may examine a private place “with the consent of the owner.” But AHS has pointed to the previous Section 59 because its lawyers have argued that rental units are in fact public places.

“What we’re fighting about here is whether or not AHS does in fact have the right to search any property that it wants at any time without asking permission from anybody or getting a warrant,” Wang and Li’s lawyer Matthew Farrell said since taking up the case last month. “Section 59, if it were to be applicable, would render the entire thing Unconstitutional and there should be a presumption towards constitutionality in the interpretation of statutes.”

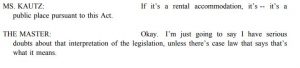

For example, in 2015 when a lawyer for AHS argued rental properties under the Act are defined as public places, it led to the following response from the judge:

“I’m just going to say I have serious doubts about that interpretation of the legislation,” he said.

Sources tell 660 NEWS there have been agreements signed between AHS and some of the tenants in which they would not have to pay court costs, so long as they gave up any potential legal action. 660 has been able to confirm one of these agreements, but it’s unclear how many there could be.

A law firm representing AHS – Carbert Waite LLP – has simply said in an email to 660 NEWS in late 2017 that AHS does not and has never acknowledged any wrongdoing. In a statement, AHS has declined to comment because matters are still before the courts:

“Alberta Health Services (AHS) cannot comment on this specific case, as it is before the courts.

However, AHS Environmental Public Health (EPH) always works to collaborate with landlords to correct problems.

AHS EPH works to ensure all public housing (including rental properties) is safe for tenants and meets Housing Regulations and Minimum Housing and Health Standards requirements.

There are many reasons why AHS EPH might inspect a housing facility. It may be in response to a complaint, a referral, or any indication that a health hazard might be present.

AHS EPH requires that owners/operators/landlords/property managers keep public housing healthy and safe for tenants,”the AHS statement says.

This is where Farrell comes in. He’s well-known for representing tenants from the Midfield Trailer Park dispute against the City of Calgary. He’s taken on Wang and Li’s case because while the episode has gone in many different directions, he says their central argument that AHS inspectors didn’t act lawfully is a strong one.

“You can’t just do this, you can’t just kick the door down and walk in to anybody’s house that you please, that’s not constitutional, the police can’t do that, surely the health inspector can’t,” he said.

Over the years, around 20 tenants have filed affidavits, alleging a wide range of inappropriate behaviour, such as the one of the woman coming out of the shower. In one attempt to inspect a property, AHS notified tenants that on December 5, 2014, inspectors would be entering, and that they would be bringing a locksmith to gain access to the property should they be unable to get inside via tenants or the property owner. There have also been multiple attempts by AHS to not simply inspect residences, but completely shut them down.

Lorian Hardcastle, an assistant professor of law at the University of Calgary and member of the O’Brien Institute for Public Health, reviewed some of the transcripts of the court proceeding in which the judge questioned AHS’ interpretation of the Act. During that proceeding, the judge also said an order to inspect the premises would only apply if tenants were first allowed to refuse access. He also expressed alarm that inspectors would simply enter without first asking the tenants to allow them in.

“In terms of the AHS interpretation of the legislation that they can theoretically inspect a rental property because it’s considered public, I think that’s a correct reading,” she said. “That being said, where there’s no public health emergency or urgency to it, there’s nothing to stop them from being reasonable.”

Hardcastle added it’s no surprise the judge would have questions about how the units were accessed.

“The order that they had from the court did say they weren’t to enter until entry had been refused, so it’s unclear to me why they showed up,” she said.

She said the argument over what constitutes a public dwelling is an area the province should explore.

“That maybe is a signal to the legislature that they need to revisit this legislation and maybe come up with something in the middle to deal with a rental property,” she said.

In this court proceeding, the judge was not ruling on the interpretation of the law, but rather whether to throw out certain amendments to a statement of claim at the request of AHS, claiming they were frivolous and vexatious. The judge denied the request in one of the few court victories for the tenants.

As for any agreements between AHS and tenants, Hardcastle said while it’s common in litigation for settlements to include non-disclosure agreements, this is a unique situation.

“I think Alberta Health is in a different position here, they’re a public actor,” she said, adding this comes down to issues of ambiguity regarding the debate between a public and a private dwelling. “Because of that, it would actually be more in their interest and certainly in the public’s interest to not push to settle this, but rather to let the court weigh in on the issues.”

ATTEMPTS TO SHUT DOWN

There have been at least two attempts to shut down properties owned by Li and Wang, including one incident in December 2013. Two days before Christmas, one of their properties received an Unfit for Human Habitation Order, reportedly due to structural integrity. Tenants describe being terrified that they would soon be on the street, one of them trying to call organizations like Samaritan’s Purse and the Red Cross for assistance. Despite the fear and order to vacate, AHS did not follow through and evict.

“AHS extended one more month, so we could live in the house until the end of January 2014. This was an indication that AHS knew the house was not as unsafe and unfit as it was made look. Otherwise, they should have evicted the tenants immediately and should not let us live for one and half more months,” the affidavit said. “We really had been frustrated for the fear of being homeless.”

On March 17th, AHS rescinded the notice.

Another attempt to shut down one of the properties was much more recent, when in late November of last year, a Forest Lawn property owned by the landlords was ordered to be shut down for 90 days, by way of a Community Safety Order under the Safer Communities and Neighbourhoods Act. Based on the evidence obtained by the SCAN Unit, it nearly happened.

The property had been investigated three times since 2014, with the order citing 173 calls to police for service between 2011 and 2017, on everything from prostitution, suspicious vehicles, drug activity and more. After a warning letter was given in August, the SCAN order was delivered three months later. On the court date in December to decide whether or not to grant the order, the SCAN lawyer described it as a rooming house, had continuous problems and it was only a matter of time until more issues would occur.

Wang and Li argued many of their tenants were referred to them by Alpha House and CUPS, with the organizations knowing some of them still had substance abuse and other issues. The landlords said they had evicted the problematic tenants since getting the warning letter in August and that there had been no issues since. The SCAN lawyer argued the judge should not purely consider the good behaviour from August onward.

The judge blasted Li and Wang for allowing their property to get out of control, as well as their lack of screening tenants. But he also recognized that they had taken the steps to change their property and instead of granting the order, adjourned the application to June.

“You folks were absentee landlords,” the judge said. “But it looks like you got your heads together.”

One of the tenants from that property has lived there for 20 years and Linne Larosee said while there certainly have been issues with some tenants, the behaviour by inspectors has been far from appropriate. She said their attempts to unlawfully inspect her unit have left her with depression, anxiety and a fear of leaving her home. She said in one case an inspector named Rikkie Ma said he had a warrant to enter and when she demanded to see it, he said he didn’t have it with him.

“He says ‘well we can do this the easy way or the hard way you better pick now,’” Larosee said, adding after he walked in behind a police officer, he went into one her roommates’ rooms. “I’ve been here 20 years, I am not going to get bullied by them and that’s exactly what they’re doing.”

“We’ve had no problems since then, so why shut us out now?” she said. “I have seven dogs, what am I supposed to do? Where am I supposed to go?”

MINOR VICTORIES

The landlords and tenants have run into a myriad of legal and financial challenges in the courts, including not being able to find counsel, let alone being able to afford them. Wang and Li have heavy accents which have caused communication issues, have no legal background and have made some claims which fall in the realm of conspiracy. They’ve accused one lawyer for AHS, Ivan Bernardo, of having a personal motivation against them and have argued for years that a report written by inspector Ayuk Eyong was actually forged.

Farrell is purely focused on the possibility that inspectors acted outside the law and orders that had been handed down from the courts.

“There’s a chance for my clients to fight over that and seek additional compensation over that and they’re going to have to look at whether or not there should be assessed costs against them,” he said.

Despite the legal challenges, there have been some small wins, such as the judge refusing to strike amendments as requested by AHS counsel and the properties not actually getting shut down. In February of 2014, Bernardo sought over $6,400 in solicitor costs and fines, arguing Wang and Li had refused to comply with an executive officer’s order requiring repairs be done to one of their properties by October 15th, 2013. Amicus counsel argued they tried to make repairs, but a troublesome tenant wouldn’t allow them into the unit and once that tenant was removed, they completed the repairs as soon as they could, although it was after the order’s deadline. The judge ruled while they didn’t meet the deadline, “I consider that the respondents took reasonable steps to try to comply with the order once the order was received. Accordingly their responsibility in regard to the breach of the court is lessened. It’s not as if they took no steps at all.” The judge imposed a fine of $500 instead. But those victories have come few and far between.

“We don’t have good sleep, we don’t have free time, all the free time used to see doctors and to prepare the court documents,” Wang said. “It’s a nightmare.”